In Karl Marx’s criticism of political economy, a commodity is any good or service transformed by the value of labour and offered as a product for general sale on the market. An exchangeable good. When contending the contemporary city, we must consider its structure as an arrangement of commodified space, as land that can be bought and sold. David Harvey (1935) explains that this process of buying and selling land is essential to the modern cities’ growth. Yet the attempt at improving the value of land often implicates antagonistic aspects such as the dismissal of existing uses and people and implementation of new practices that encourage consumption. This evidence gives rise to the notion of privately owned public space as a strategy for urban regeneration.

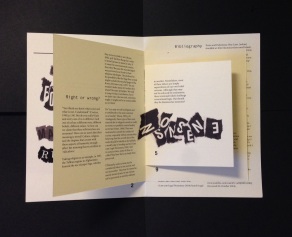

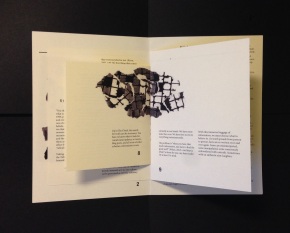

As a result of the mid 1970s economic decline, vast decaying areas of the city previously settled by factories and docklands became part of colossal regeneration schemes funded by local authorities who sold land to private companies to ensure financial triumph. The archetype of this means is Canary Wharf, a major business district located in Tower Hamlets, east London. The images above demonstrate the space preceding and succeeding renewal plans which allowed unrestricted development of the docklands, formerly engaged in a strategic avenue for the shipping of goods. As academic and journalist Anna Minton discusses in her book ‘Ground Control’ (2011), “previously, the government and local councils ‘owned’ the city on behalf of us, the people. Now more and more of the city is owned by investors, and its central purpose is profit.” Money, money, money.

This measure has generated what is debated as the phenomenon of gentrification. The process by which increased property values are displacing lower income families (working class and unskilled households) and small businesses, making space for a middle class demographic. And although the gentrified city is seen as successful, prosperous and creative, once the original occupiers are entirely displaced from residential neighbourhoods, “the whole social character of the district is changed” (Glass, 1964). Thus who does regeneration truly benefit?

Urban renewal and the invasion of the middle class has been perceived as an economic engine on one hand, yet a mechanism for control on the other. The original premise was that if areas of the cities were rehabilitated by bringing revenue, areas nearby would benefit too, in a ‘trickle down’ effect. The reality however, is that neighbourhoods are demolished, taking identity and authenticity down with them.

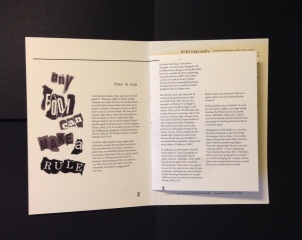

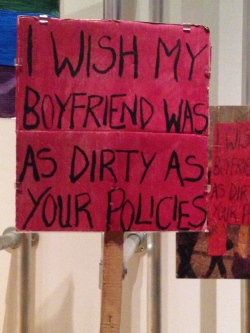

What I find most disquieting in respect to todays urban society, is the role culture plays within the city as a tool for authority. As urban sociologist Sharon Zukin (1995) argues, “culture is more and more the business of cities – the basis of their tourist attractions and their unique, competitive edge”. In an endeavour to contend tourism and investment, cities are increasingly striving to enhance their portrait as a hub of cultural innovation; trendy cafe’s, lavish restaurants, art galleries, selling images on a global scale. As the private sector takes command over public spaces, design is adopted as an implicit codex of inclusion and exclusion, getting rid of the undesirables. A measure to determine who belongs in certain spaces and who doesn’t. Zukin labels this incident as ‘pacification by cappuccino’, an ironic scenario in which urban environment is geared towards consumption of those who can afford consuming. And what happens to everyone else I wonder?